In addition to defining individual parts of your page (such as "a paragraph" or "an image"), HTML also boasts a number of block level elements used to define areas of your website (such as "the header", "the navigation menu", "the main content column"). This article looks into how to plan a basic website structure, and write the HTML to represent this structure.

| Prerequisites: | Basic HTML familiarity, as covered in Getting started with HTML. HTML text formatting, as covered in HTML text fundamentals. How hyperlinks work, as covered in Creating hyperlinks. |

|---|---|

| Objective: | Learn how to structure your document using semantic tags, and how to work out the structure of a simple website. |

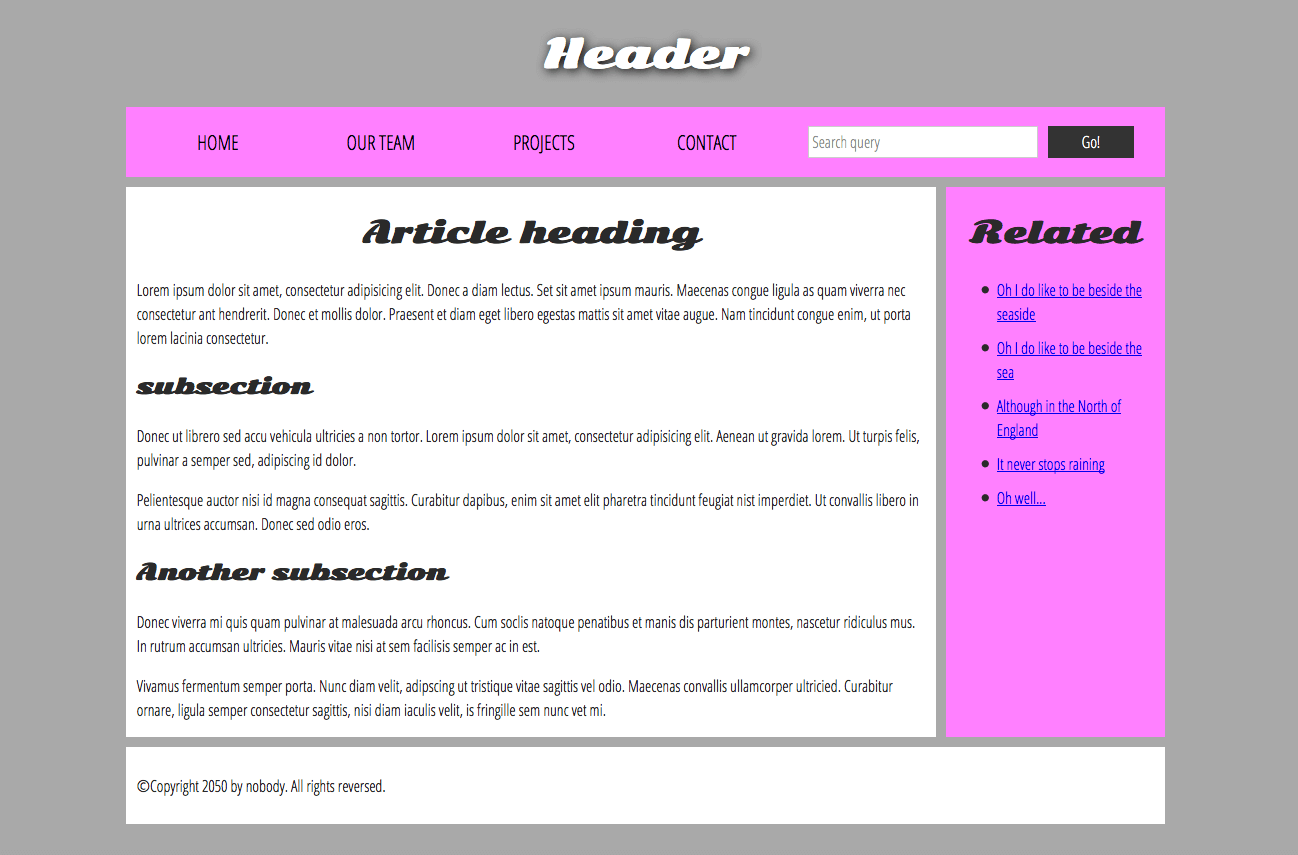

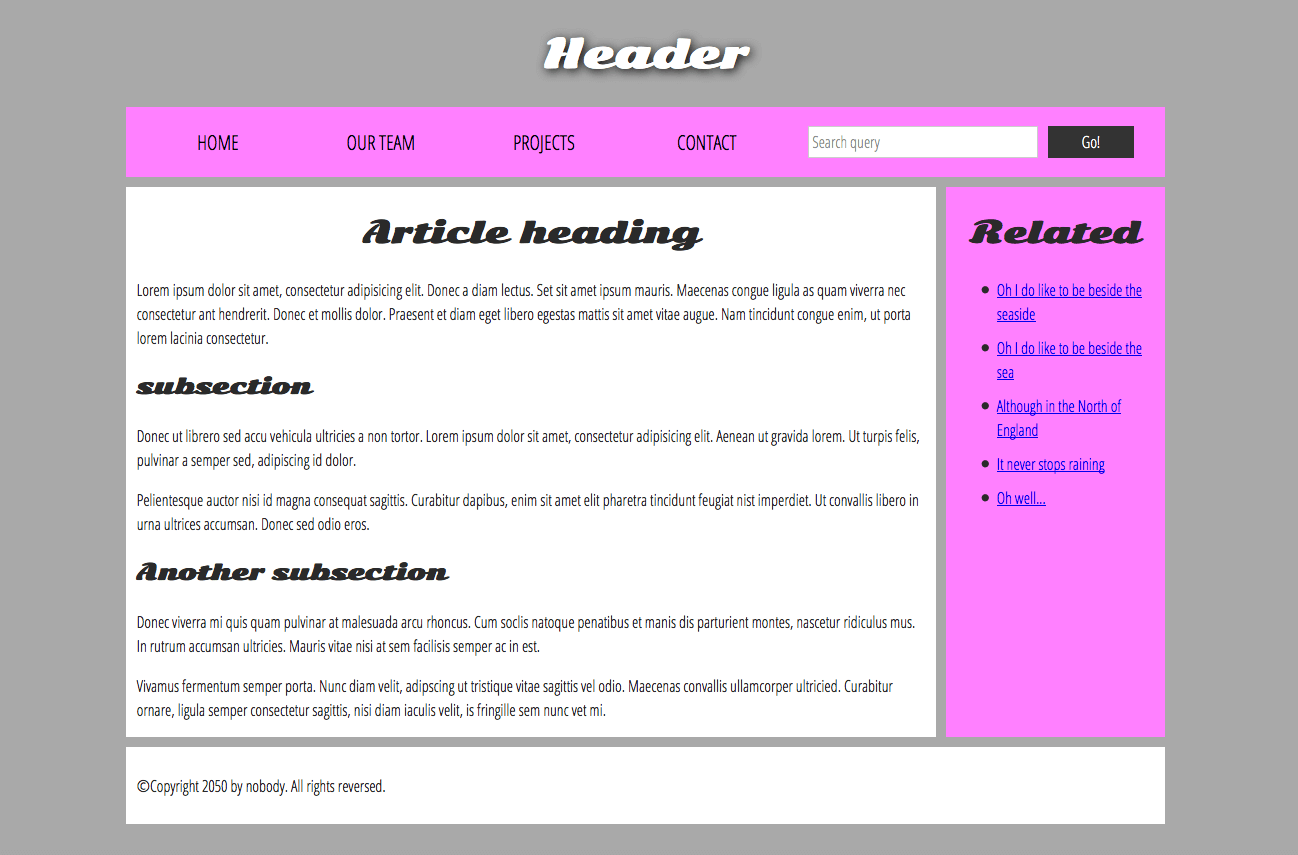

Webpages can and will look pretty different from one another, but they all tend to share similar standard components, unless the page is displaying a fullscreen video or game, is part of some kind of art project, or is just badly structured:

Usually a big strip across the top with a big heading, logo, and perhaps a tagline. This usually stays the same from one webpage to another.

Links to the site's main sections; usually represented by menu buttons, links, or tabs. Like the header, this content usually remains consistent from one webpage to another — having inconsistent navigation on your website will just lead to confused, frustrated users. Many web designers consider the navigation bar to be part of the header rather than an individual component, but that's not a requirement; in fact, some also argue that having the two separate is better for accessibility, as screen readers can read the two features better if they are separate.

A big area in the center that contains most of the unique content of a given webpage, for example, the video you want to watch, or the main story you're reading, or the map you want to view, or the news headlines, etc. This is the one part of the website that definitely will vary from page to page!

Some peripheral info, links, quotes, ads, etc. Usually, this is contextual to what is contained in the main content (for example on a news article page, the sidebar might contain the author's bio, or links to related articles) but there are also cases where you'll find some recurring elements like a secondary navigation system.

A strip across the bottom of the page that generally contains fine print, copyright notices, or contact info. It's a place to put common information (like the header) but usually, that information is not critical or secondary to the website itself. The footer is also sometimes used for SEO purposes, by providing links for quick access to popular content.

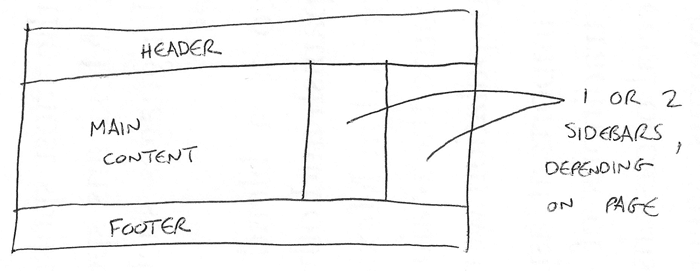

A "typical website" could be structured something like this:

Note: The image above illustrates the main sections of a document, which you can define with HTML. However, the appearance of the page shown here - including the layout, colors, and fonts - is achieved by applying CSS to the HTML.

In this module we're not teaching CSS, but once you have an understanding of the basics of HTML, try diving into our CSS first steps module to start learning how to style your site.

The simple example shown above isn't pretty, but it is perfectly fine for illustrating a typical website layout example. Some websites have more columns, some are a lot more complex, but you get the idea. With the right CSS, you could use pretty much any elements to wrap around the different sections and get it looking how you wanted, but as discussed before, we need to respect semantics and use the right element for the right job.

This is because visuals don't tell the whole story. We use color and font size to draw sighted users' attention to the most useful parts of the content, like the navigation menu and related links, but what about visually impaired people for example, who might not find concepts like "pink" and "large font" very useful?

Note: Roughly 8% of men and 0.5% of women are colorblind; or, to put it another way, approximately 1 in every 12 men and 1 in every 200 women. Blind and visually impaired people represent roughly 4-5% of the world population (in 2015 there were 940 million people with some degree of vision loss, while the total population was around 7.5 billion).

In your HTML code, you can mark up sections of content based on their functionality — you can use elements that represent the sections of content described above unambiguously, and assistive technologies like screen readers can recognize those elements and help with tasks like "find the main navigation", or "find the main content." As we mentioned earlier in the course, there are a number of consequences of not using the right element structure and semantics for the right job.

To implement such semantic mark up, HTML provides dedicated tags that you can use to represent such sections, for example:

Our example seen above is represented by the following code (you can also find the example in our GitHub repository). We'd like you to look at the example above, and then look over the listing below to see what parts make up what section of the visual.

doctype html> html lang="en-US"> head> meta charset="utf-8" /> meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width" /> title>My page titletitle> link href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Open+Sans+Condensed:300|Sonsie+One" rel="stylesheet" /> link rel="stylesheet" href="style.css" /> head> body> header> h1>Headerh1> header> nav> ul> li>a href="#">Homea>li> li>a href="#">Our teama>li> li>a href="#">Projectsa>li> li>a href="#">Contacta>li> ul> form> input type="search" name="q" placeholder="Search query" /> input type="submit" value="Go!" /> form> nav> main> article> h2>Article headingh2> p> Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Donec a diam lectus. Set sit amet ipsum mauris. Maecenas congue ligula as quam viverra nec consectetur ant hendrerit. Donec et mollis dolor. Praesent et diam eget libero egestas mattis sit amet vitae augue. Nam tincidunt congue enim, ut porta lorem lacinia consectetur. p> h3>Subsectionh3> p> Donec ut librero sed accu vehicula ultricies a non tortor. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Aenean ut gravida lorem. Ut turpis felis, pulvinar a semper sed, adipiscing id dolor. p> p> Pelientesque auctor nisi id magna consequat sagittis. Curabitur dapibus, enim sit amet elit pharetra tincidunt feugiat nist imperdiet. Ut convallis libero in urna ultrices accumsan. Donec sed odio eros. p> h3>Another subsectionh3> p> Donec viverra mi quis quam pulvinar at malesuada arcu rhoncus. Cum soclis natoque penatibus et manis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. In rutrum accumsan ultricies. Mauris vitae nisi at sem facilisis semper ac in est. p> p> Vivamus fermentum semper porta. Nunc diam velit, adipscing ut tristique vitae sagittis vel odio. Maecenas convallis ullamcorper ultricied. Curabitur ornare, ligula semper consectetur sagittis, nisi diam iaculis velit, is fringille sem nunc vet mi. p> article> aside> h2>Relatedh2> ul> li>a href="#">Oh I do like to be beside the seasidea>li> li>a href="#">Oh I do like to be beside the seaa>li> li>a href="#">Although in the North of Englanda>li> li>a href="#">It never stops raininga>li> li>a href="#">Oh well…a>li> ul> aside> main> footer> p>©Copyright 2050 by nobody. All rights reversed.p> footer> body> html>

Take some time to look over the code and understand it — the comments inside the code should also help you to understand it. We aren't asking you to do much else in this article, because the key to understanding document layout is writing a sound HTML structure, and then laying it out with CSS. We'll wait for this until you start to study CSS layout as part of the CSS topic.

It's good to understand the overall meaning of all the HTML sectioning elements in detail — this is something you'll work on gradually as you start to get more experience with web development. You can find a lot of detail by reading our HTML element reference. For now, these are the main definitions that you should try to understand:

Each of the aforementioned elements can be clicked on to read the corresponding article in the "HTML element reference" section, providing more detail about each one.

Sometimes you'll come across a situation where you can't find an ideal semantic element to group some items together or wrap some content. Sometimes you might want to just group a set of elements together to affect them all as a single entity with some CSS or JavaScript. For cases like these, HTML provides the and elements. You should use these preferably with a suitable class attribute, to provide some kind of label for them so they can be easily targeted.

p> The King walked drunkenly back to his room at 01:00, the beer doing nothing to aid him as he staggered through the door. span class="editor-note"> [Editor's note: At this point in the play, the lights should be down low]. span> p>

In this case, the editor's note is supposed to merely provide extra direction for the director of the play; it is not supposed to have extra semantic meaning. For sighted users, CSS would perhaps be used to distance the note slightly from the main text.

div class="shopping-cart"> h2>Shopping carth2> ul> li> p> a href="">strong>Silver earringsstrong>a>: $99.95. p> img src="../products/3333-0985/thumb.png" alt="Silver earrings" /> li> li>…li> ul> p>Total cost: $237.89p> div>

This isn't really an , as it doesn't necessarily relate to the main content of the page (you want it viewable from anywhere). It doesn't even particularly warrant using a , as it isn't part of the main content of the page. So a is fine in this case. We've included a heading as a signpost to aid screen reader users in finding it.

Warning: Divs are so convenient to use that it's easy to use them too much. As they carry no semantic value, they just clutter your HTML code. Take care to use them only when there is no better semantic solution and try to reduce their usage to the minimum otherwise you'll have a hard time updating and maintaining your documents.

Two elements that you'll use occasionally and will want to know about are and .

creates a line break in a paragraph; it is the only way to force a rigid structure in a situation where you want a series of fixed short lines, such as in a postal address or a poem. For example:

p> There once was a man named O'Dellbr /> Who loved to write HTMLbr /> But his structure was bad, his semantics were sadbr /> and his markup didn't read very well. p>

Without the

elements, the paragraph would just be rendered in one long line (as we said earlier in the course, HTML ignores most whitespace); with

elements in the code, the markup renders like this:

p> Ron was backed into a corner by the marauding netherbeasts. Scared, but determined to protect his friends, he raised his wand and prepared to do battle, hoping that his distress call had made it through. p> hr /> p> Meanwhile, Harry was sitting at home, staring at his royalty statement and pondering when the next spin off series would come out, when an enchanted distress letter flew through his window and landed in his lap. He read it hazily and sighed; "better get back to work then", he mused. p>

Would render like this:

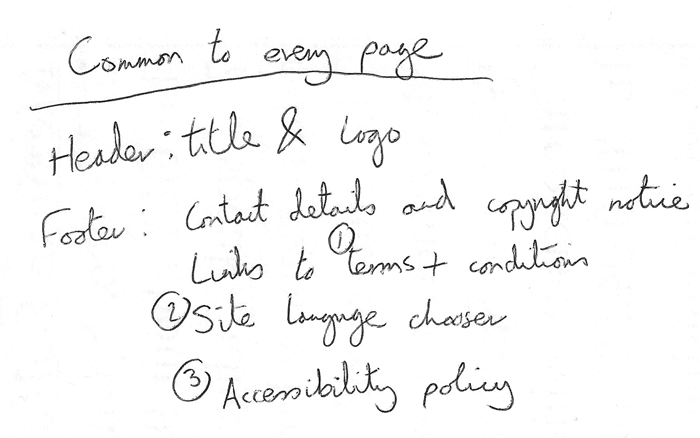

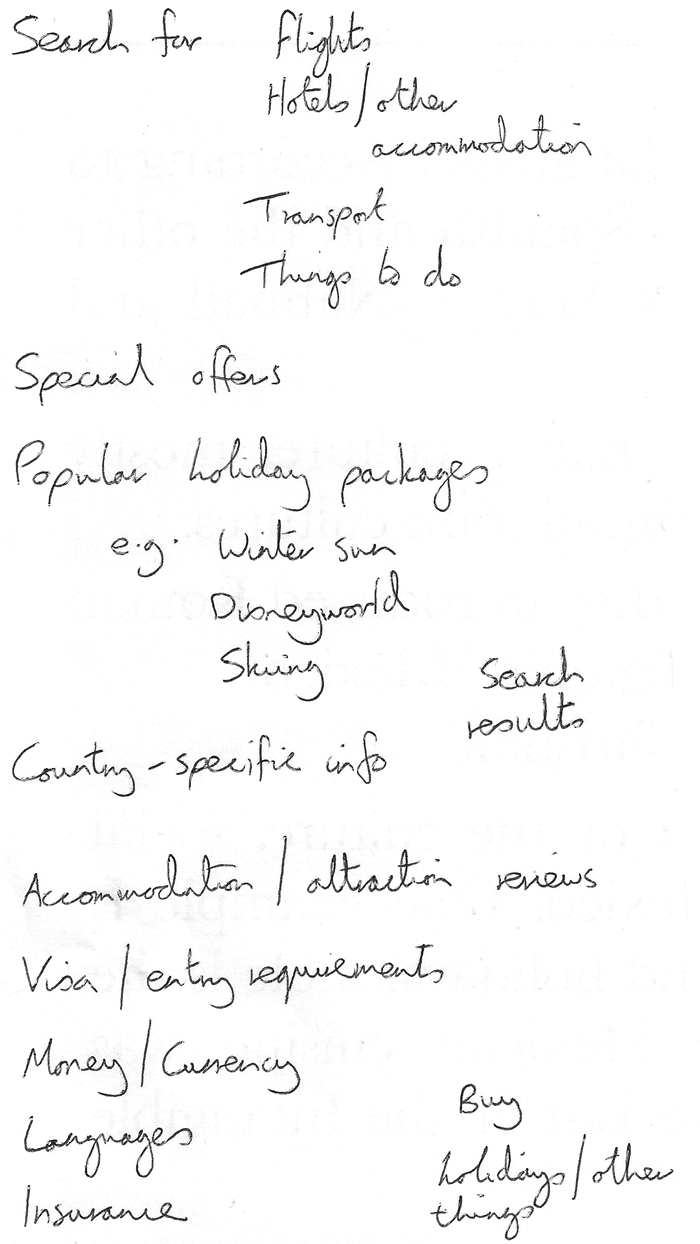

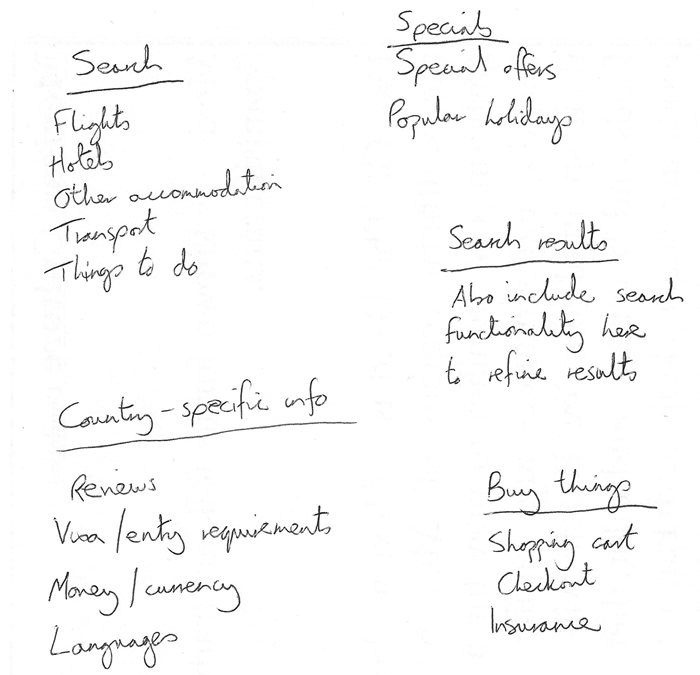

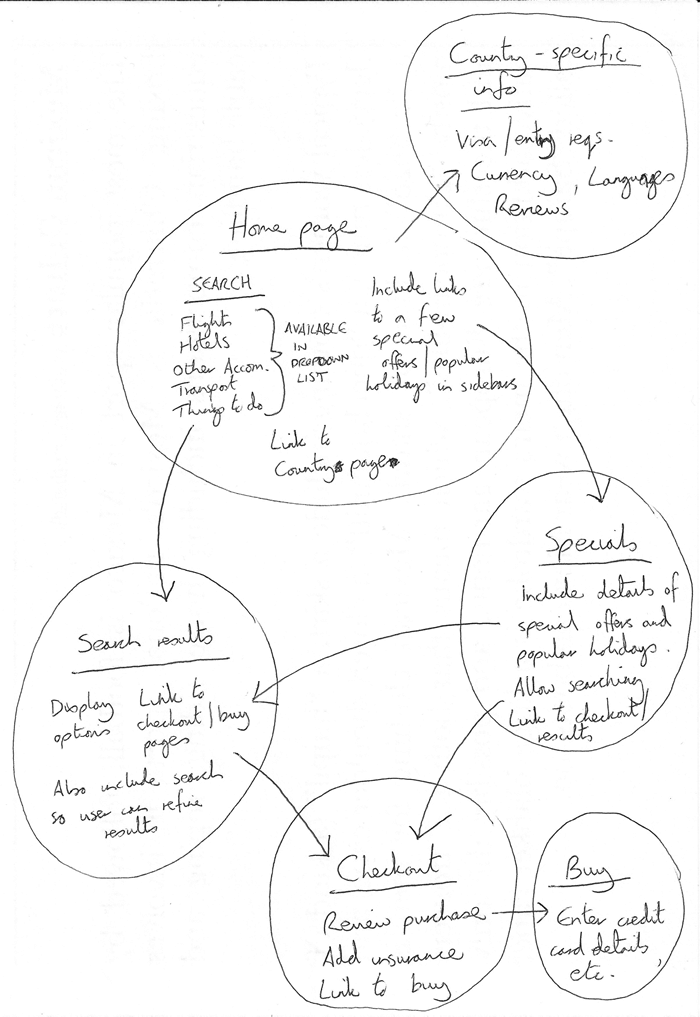

Once you've planned out the structure of a simple webpage, the next logical step is to try to work out what content you want to put on a whole website, what pages you need, and how they should be arranged and link to one another for the best possible user experience. This is called Information architecture. In a large, complex website, a lot of planning can go into this process, but for a simple website of a few pages, this can be fairly simple, and fun!

Try carrying out the above exercise for a website of your own creation. What would you like to make a site about?

Note: Save your work somewhere; you might need it later on.

At this point, you should have a better idea about how to structure a web page/site. In the next article of this module, we'll learn how to debug HTML.