Help our mission to provide free history education to the world! Please donate and contribute to covering our server costs in 2024. With your support, millions of people learn about history entirely for free every month.

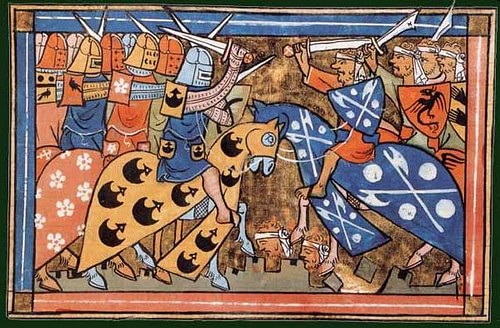

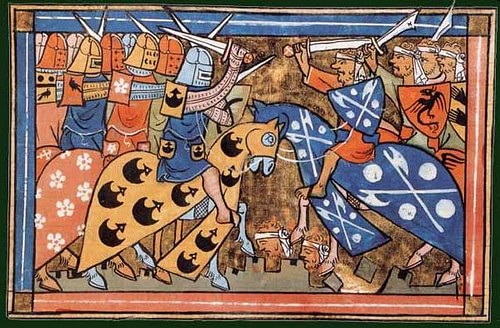

$ 12319 / $ 18000The armies of the Crusades (11th-15th centuries CE), which saw Christians and Muslims struggle for control of territories in the Middle East and elsewhere, could involve over 100,000 men on either side who came from all over Europe to form the Christian armies and from all over western Asia and North Africa for the Muslim ones. The Christians had the advantage of disciplined and well-armoured knights while the Muslims often used light cavalry and archers to great effect. Over time both sides would learn from each other, adopting weapons and tactics to their own advantage. Huge resources were invested in the Crusades on both sides and while Christian armies were successful in Iberia and the Baltic, in the arena that mattered most, the Holy Land, it was perhaps the superior tactics and greater concern with logistics that ensured the armies of the various Muslim states eventually saw off the Christian threat.

European armies throughout the Crusades were a mix of heavily armoured knights, light cavalry, bowmen, crossbowmen, slingers, and regular infantry armed with spears, swords, axes, maces and any other weapon of choice. Most knights swore allegiance to one particular leader and, as many Crusades were led by multiple nobles or even kings and emperors, any Crusade army was usually a cosmopolitan mix of nationalities and languages. Although an overall leader was typically appointed before the campaign, the power and wealth of the nobles involved meant that disputes over strategy were frequent. With the exception of the first two crusades (1095-1102 CE & 1147-1149 CE), the armies were almost entirely raised on a feudal basis - conscripted men from the lands of barons - with a significant section of mercenaries, usually infantry, added on. Noted mercenary groups in Europe came from Brittany and the Low Countries while Italian crossbowmen were highly regarded. When kings were involved they could call on conscription of any able-bodied man to serve the needs of the crown but these troops were poorly trained and equipped.

AdvertisementKnights of the military orders were sometimes a little too enthusiastic on the battlefield but their valour & worth to the crusading cause is undisputed.

The transport of armies to where they were needed was mostly provided by the ships of the Italian states of Genoa, Pisa and Venice. Sometimes, these cities would also provide troops and ships for active service in the campaign itself. Naturally, an army in the field numbering tens of thousands of fighting men required a large number of non-combatant personnel such as baggage handlers, labourers, carpenters, cooks, and priests, while knights brought along their own personal squires and servants.

The four Crusader States in the Middle East were the Principality of Antioch, the County of Edessa, the County of Tripoli, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Led by (in theory) the latter, the states raised their own armies based on feudal tenants, free men and mercenaries. Rulers often granted estates to nobles in return for a fixed quota of fighting men in times of war. The Crusader States could not rely on conscripting the local population as they were mostly Muslim and had no training anyway. Due to the small western population, then, the Crusader States were perpetually short of fighting men – they could muster a maximum of 1500 knights, for example – and they became heavily reliant on the military orders in the region. The employment of mercenaries obviously depended on the funds available but at least the Crusader States did receive occasional payments from European monarchs. These rulers preferred that method of assistance rather than sending an actual army to still comply with their perceived moral duty as Christian sovereigns to defend the Holy Land. Another problem was the relatively equal status between the barons and king of the Kingdom of Jerusalem which led to much squabbling and even instances of one or more Crusader States temporarily opting for neutrality rather than support the common cause of defence.

AdvertisementInitially formed to protect and offer medical care for pilgrims travelling through the Holy Land, the military orders such as the Knights Templar, Knights Hospitaller and Teutonic Knights soon established themselves as an invaluable military presence in the region. Knights of the military orders, who were recruited from across Europe and lived much like monks, were frequently given the most dangerous passes and strategically valuable castles to garrison and they provided several hundred knights for most Crusade field armies. With the best training and equipment, they were the elite force of the Crusaders and their frequent execution if ever captured is a testimony to the respect they had from their opponents – they were simply too skilled and fanatical to be allowed back onto any future battlefield. The one drawback of the orders was their total independence which sometimes resulted in arguments with rulers of the Crusaders States and leaders of Crusader armies over strategy and alliances. Knights of the military orders were sometimes a little too enthusiastic on the battlefield and could make rash, unsupported charges but their valour and worth to the crusading cause is undisputed. Other military orders soon sprang up in Europe, especially in the Iberian peninsula during the Reconquista against the Muslim Moors and the big three already mentioned spread their tentacles of power throughout mainland Europe. The Teutonic Knights were especially effective and carved out their own state in Prussia and beyond during the Northern Crusades against European pagans.

By the 12th century CE the Byzantine Empire was in decline and its army reflected this situation by being mostly composed of mercenaries. Nevertheless, at the time of the First Crusade, the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118 CE) could muster an army of around 70,000 when required. In the early Crusades, the Empire did contribute to Crusader armies (before becoming itself the victim of the Fourth Crusade, 1202-1204 CE), providing its various units of mercenaries which included Turkish light cavalry, the Varangian Guards of Anglo-Saxon- and Viking descendants who wielded huge battle-axes, Serbs, Hungarians and Rus infantry. All were highly organised and well-trained and especially useful were the Byzantine engineers who brought invaluable expertise to siege warfare.

AdvertisementMuslim armies generally followed a similar pattern of recruitment as European armies and were made up of an elite bodyguard (askars), feudal levies from such key cities as Mosul, Aleppo and Damascus, allied troops, volunteers and mercenaries. In the Muslim armies, there were units of cavalry, which could include mounted archers, and infantry armed with spears, crossbows or bows and protected most often by a circular shield. Seljuk cavalry typically wore lamellar armour which was made of overlapping rows of small iron or hardened leather plates.

It was a common Seljuk tactic to engage the enemy, fire off a lethal barrage of arrows & then withdraw as quickly as possible to minimise losses.

The Seljuks dominated western Asia from the mid-11th century CE and their armies were notable for the large contingents of highly skilled mounted archers. It was a common tactic to engage the enemy, fire off a lethal barrage of arrows and then withdraw as quickly as possible to minimise losses. With any luck, the enemy might also be tempted to launch a risky cavalry charge in pursuit when the archers could turn back and attack again or fire down on the enemy from a position of ambush.

The Fatimid Caliphate (909-1171 CE) was based in Egypt and relied heavily on mercenary troops but their vast wealth ensured they could field very large armies of reasonably well-trained and well-equipped infantry which included contingents of Sudanese archers. Cavalry was usually composed of a mix of scimitar-wielding Arabs, Bedouins and Berbers. The Fatimid army might have been the best in the Muslim world of the time but they were somewhat off the pace compared to the Crusaders in terms of weapons, armour and tactics; their successors the Ayyubids, though, would soon catch up.

Advertisement

The Ayyubid Dynasty (1171-1260 CE) was formed by the great Muslim leader Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193 CE). Taking over the armies of the Fatimids, Saladin greatly increased efficiency and selected as his main elite force around 1,000 Kurdish warriors, the Mamluks, who had been trained since childhood and who had especially strong ties to their trainer-commander. There was, too, a significant contingent of Kipchak Turkish slave warriors taken from the Russian steppe. The rest of the army was composed of troops levied from the regional governors across the Ayyubid empire in Egypt, Syria and Jazira (northern Iraq). Saladin's infantry was particularly noted for its discipline, a feature at that time usually only associated with elite cavalry units.

As already noted, the Mamluks formed a vital part of Ayyubid armies and they became so expert at warfare that they overthrew their masters in the mid-13th century CE and formed the Mamluk Sultanate (1250-1517 CE). They employed mercenaries such as Bedouins, Turks, Armenians and Kurds in their armies which were so large that the Crusaders became extremely wary of direct battles. Mamluk cavalry often wore metal helmets engraved with verses of the Koran, wore a piece of chain mail over the lower half of their faces and carried a kite-shaped shield. Another interesting feature of the Mamluk field army was multiple corps of musicians who played trumpets and drums which contributed to creating panic amongst the enemy, especially their horses. The sultan's personal bodyguard had its own band of 4 oboe (hautbois) players, 20 trumpeters and 44 drummers.

The Moors who controlled most of the southern half of Iberia and faced the Crusaders of the Reconquista favoured hit and run tactics using lightly armed cavalry whose preferred weapons were the lance and javelin. Even infantry troops, typically the frontline of a unit, had throwing javelins while the rest were armed with long spears. Berbers carried a distinctive heart-shaped shield, the adarga, while Moorish cavalry had a kite-shaped shield similar to their European counterparts.

Advertisement

By the end of the 14th century CE, a new foe was identified as a legitimate target for a Crusade: the Ottoman Turks. The Ottomans had two elite units of note. The Janissary Guards were a corps of infantry archers formed from conscripted Christians who were given military training from childhood. Secondly, the elite sipahis was a cavalry unit whose members were promised the right to estates and tax revenues for any success on the battlefield. The Ottomans also used gunpowder weapons from the 15th century CE. Some of their cannons were huge measuring 9 metres (30 ft) in length and able to fire a ball weighing 500 kilos (1100 lbs) over a distance of 1.5 km (1600 yards).

Crusader armies were organised into several divisions each led by a senior commander who was expected to follow the pre-arranged battle plan and the orders of the overall field commander. Communication was achieved through banners (which were especially used as rallying points) or verbal orders but in the noise, dust and chaos of battle, it was safer if everyone avoided the temptation for rash charges without proper support. Not that this was always avoided as many defeats during the Crusades were largely down to one element of an army taking too high a risk in an independent action.

In terms of tactics, infantry was typically armed with spears and crossbows and protected by padded armour. They were so arranged in combat to form a protective encirclement of their own heavy cavalry of knights. The idea was that enemy missiles would be prevented from harming the horses if they had a protective barrier of more expendable infantrymen. The same strategy was used when a Crusader army was on the march. In battle, infantry was divided into small companies while knights typically operated in groups of 20-25.

Knights were the elite part of Crusader armies. Protected by chain and then plate armour, and riding a similarly protected horse, they could charge the enemy in a very tight formation with lances and break up the enemy lines, cutting down opponents with their long swords. Sergeants, the rank one level down from a knight, may also have formed cavalry units but they were used as infantry, too. Initially, heavy cavalry brought significant victories for the Europeans but eventually, the Muslim armies adapted and even adopted some of their tactics, with the Ayyubids fielding their own heavy cavalry units, for example.

Knights made up only around 10% of any Crusader army and heavy cavalry needed both reasonably level and dry ground to operate effectively. Consequently, a well-disciplined and numerically superior body of infantry armed with crossbows could sometimes hold their own against them in battle. It should also be remembered that the wars of the Crusades most often involved sieges of fortified cities; field battles were rare and such was the gamble involved in them that defeat in a single day could spell the end of a particular campaign. In addition, a favourite Muslim tactic was to harass the enemy with light cavalry and mounted archers so the knights never got the chance to perform a disciplined charge against massed enemy lines. All in all, then, the role of heavily armoured knights was not quite as great an influence on victory as literature and subsequent legends would have us believe.

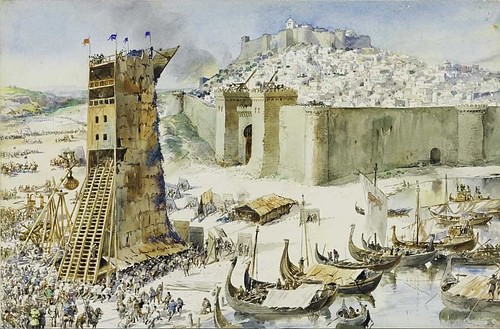

As noted, siege warfare was a major part of Crusade warfare and then knights were expected to pitch in with everyone else and try and bring a city or fortified camp to its knees as quickly as possible. Both Christian and Muslim armies found themselves the attackers and defenders throughout the many campaigns. Catapults launched huge boulders and flaming missiles against the defenders. Sometimes, too, projectiles of a more psychological nature such as decapitated heads were lobbed over the walls. There were even the really unscrupulous commanders who sanctioned the firing of diseased corpses of animals and humans into the laps of the enemy. Siege towers and battering rams permitted a direct attack on the walls themselves. Undermining walls was a tactic where specialised engineers dug tunnels and set fires in them to bring the foundations of towers crashing down. Meanwhile, the defenders would launch rocks and flammable liquids onto the attackers and send out sorties of heavy cavalry to disrupt the attacker's camps.

Love History?Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Logistics has always been a crucial aspect of warfare that can spell defeat or win victory regardless of an army's fighting skills and a commander's knowledge of strategy. Unfortunately for the Crusaders, medieval Europe had long since lost the skill of battle logistics, those having disappeared following the demise of the Romans. The skills would have to be relearned in the Middle East, especially so considering the often harsh and arid climate and terrain where living off the land was usually not an option. Many a Crusader army was defeated simply because it could not find adequate food and water and men died of scurvy or starvation. Another frequent killer was bacterial disease, especially rife in the filthy army camps of siege armies which typically lacked adequate sanitation, clean water and treatment of the dead.

A lack of forward planning was also often evident with the Crusaders' sieges being carried out without proper siege equipment or rivers navigated without reliable boats. There were exceptions: Richard I of England (1189-1199 CE) was a meticulous planner and not only did he ship catapults to the Middle East but also the huge boulders they needed as ammunition. The armies of the Crusader States were much better at this aspect of warfare and supply columns and chains of supply bases were sometimes established but again and again; when European leaders took the field they often simply ignored the particular challenges of the terrain they hoped to win victory on. In contrast, the Muslims were far better in this department and maintained excellent supply columns using thousands of mules and camels which included doctors and medical equipment. In addition, the Muslim armies frequently worsened the Crusaders' situation by spoiling wells, rounding up livestock and destroying crops. Finally, a feature of the Muslim world which often proved useful during the Crusades was the well-established communication system of staging posts spread across the region connected by trained pigeons. With messages being carried on the wing over distances of 1500 km the movements of the enemy could be quickly reported and appropriate responses planned and executed.